ResearchNews Videos

But HOW Does Carbon Dioxide Trap Heat?

Flashback

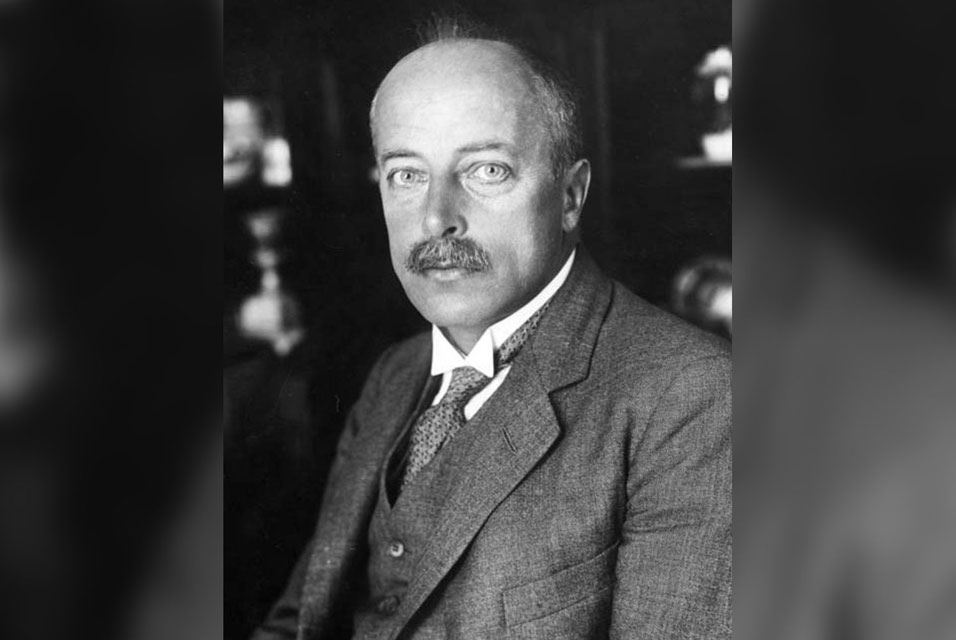

On a day like today, Nobel Prize laureate Max von Laue died

April 24, 1960. Max Theodor Felix von Laue (9 October 1879 - 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals. In addition to his scientific endeavors with contributions in optics, crystallography, quantum theory, superconductivity, and the theory of relativity, Laue had a number of administrative positions which advanced and guided German scientific research and development during four decades. A strong objector to Nazism, he was instrumental in re-establishing and organizing German science after World War II. From 1914 to 1919, Laue was at the University of Frankfurt as ordinarius professor of theoretical physics. He was engaged in vacuum tube development, at the University of Würzburg, for use in military telephony and wireless communications from 1916.

|

Tell a Friend

Dear User, please complete the form below in order to recommend the ResearchNews newsletter to someone you know.

Please complete all fields marked *.

Sending Mail

Sending Successful