ResearchNews Videos

Not all monkeys are fooled by magic.

Flashback

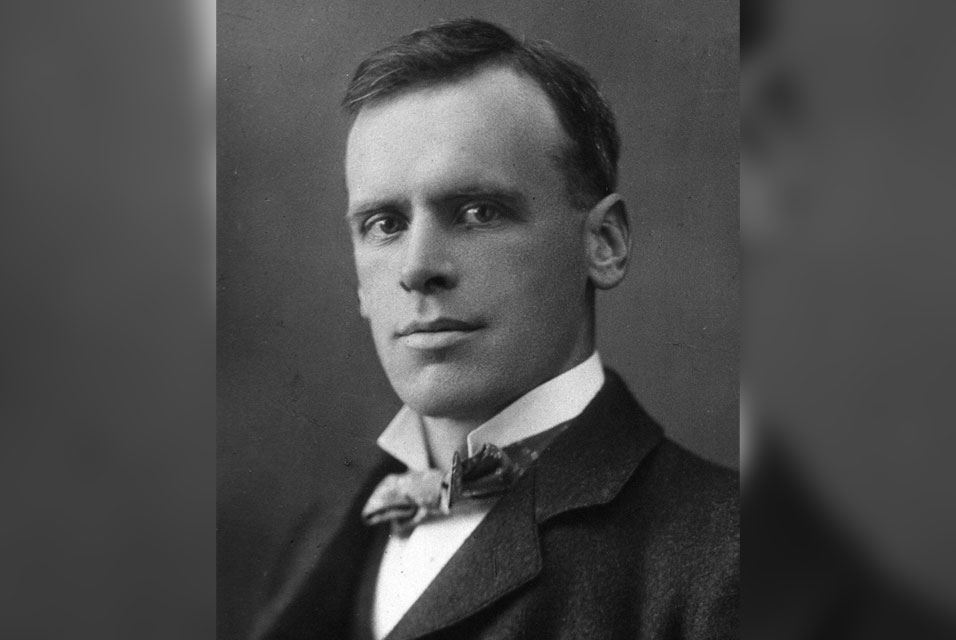

On a day like today, English physiologist and academic Ernest Starling was born

April 17, 1866. Ernest Henry Starling (17 April 1866 - 2 May 1927) was a British physiologist who contributed many fundamental ideas to this subject. These ideas were important parts of the British contribution to physiology, which at that time led the world. He made at least four significant contributions: 1. In the capillary, water is forced out through the pores in the wall by hydrostatic pressure and driven in by the osmotic pressure of plasma proteins (or oncotic pressure). These opposing forces approximately balance; which is known as Starling's Principle. 2. The discovery of the hormone secretin—with his brother-in-law William Bayliss—and the introduction of the word hormone. 3. The analysis of the heart's activity as a pump, which is known as the Frank–Starling law. 4. Several fundamental observations on the action of the kidneys. These include evidence for the existence of vasopressin, the anti-diuretic hormone. He also wrote the leading textbook of physiology in English, which ran through 20 editions.

|

Tell a Friend

Dear User, please complete the form below in order to recommend the ResearchNews newsletter to someone you know.

Please complete all fields marked *.

Sending Mail

Sending Successful