RICHLAND, WA.- In the world of electricity, copper is king—for now. That could change with new research from

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory that is serving up a recipe to increase the conductivity of aluminum, making it economically competitive with copper. This research opens the door to experiments that—if fully realized—could lead to an ultra-conductive aluminum alternative to copper that would be useful in markets beyond transmission lines, revolutionizing vehicles, electronics, and the power grid.

"What if you could make aluminum more conductive—even 80% or 90% as conductive as copper? You could replace copper and that would make a massive difference because more conductive aluminum is lighter, cheaper, and more abundant," said Keerti Kappagantula, PNNL materials scientist and co-author on the research. "That's the big picture problem that we're trying to solve."

Copper vs. aluminum

Copper demand is fast outpacing its current availability, driving up its cost. Copper is a great electrical conductor—it's used in everything from handheld electronics to underwater transmission cables that power the internet—but there's no escaping the fact that copper is becoming less available and more expensive. These challenges are only expected to get worse with the rising number of electric vehicles (EVs), which need twice as much copper as traditional vehicles. Plus, copper is heavy, which drives down EV efficiency.

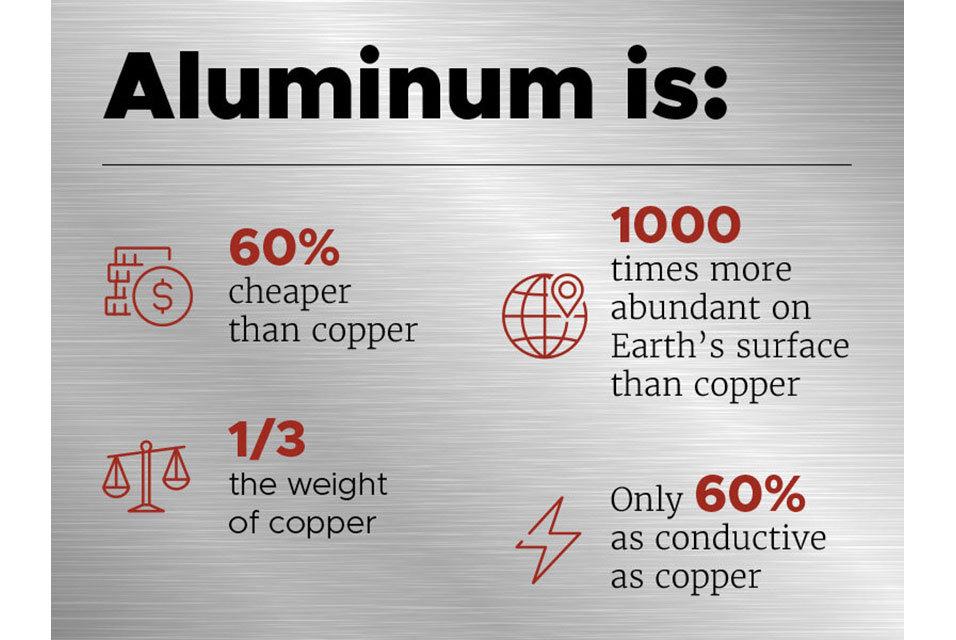

Aluminum is just one-third the price and weight of copper, but it is only about 60% as conductive. Aluminum's relatively low conductivity can be a limitation in some real-world applications.

"Conductivity is key because a lighter weight wire with equivalent conduction can be used to design lighter motors and other electrical components, so your vehicle can potentially go longer distances," said Kappagantula. "Everything from a car's electronics to energy generation to transmitting that energy to your home via the grid to charge your car's battery—anything that runs on electricity—it can all become more efficient."

Increasing aluminum's conductivity would be a game-changer.

"For years, we thought metals couldn't be made more conductive. But that's not the case," explained Kappagantula. "If you alter the structure of the metal and introduce the right additives, you can indeed influence its properties."

To begin figuring out just how much aluminum conductivity could be increased, Kappangantula and PNNL post-doctoral scholar Aditya Nittala teamed up with Distinguished Professor David Drabold and graduate student Kashi Subedi of Ohio University to identify the effects of temperature and structural defects in aluminum conductivity and develop an atom-by-atom recipe to increase its conductivity.

A model success

This type of molecular simulation had never been done for metals before, so the researchers had to get creative. They looked to semiconductors for inspiration because previous research had successfully simulated conductivity in these silicon-based materials and some metal oxides. The team adapted these concepts to work with aluminum and simulated what would happen to the metal's conductivity if individual atoms in its structure were removed or rearranged. These tiny changes added up to big gains in total conductivity.

The model's ability to simulate real-world conditions surprised even the team. "We didn't think that these results would be this close to reality," said Kappagantula. "This model simulation that's based on the atomic structure and its different states is so precise—I was like, 'Wow, that's right on target.' It's very exciting."

With a theoretical recipe to alter metal conductivity now clear, the researchers plan to see how much they can increase the conductivity of aluminum in the laboratory to match theory with experimental results. They are also exploring the possibility of increasing the conductivity of other metals using the same simulations.

The research is published in Physical Review B, and the team expects that more conductive aluminum would have far-reaching implications—any application that uses electricity or copper could benefit from the development of affordable, lightweight, ultra-conductive aluminum.