CLEVELAND, OH.- Case Western Reserve University researchers have identified a mechanism in brain tissue that may explain why women are more vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease—a finding that they say could help lead to new medicines to treat the disease.

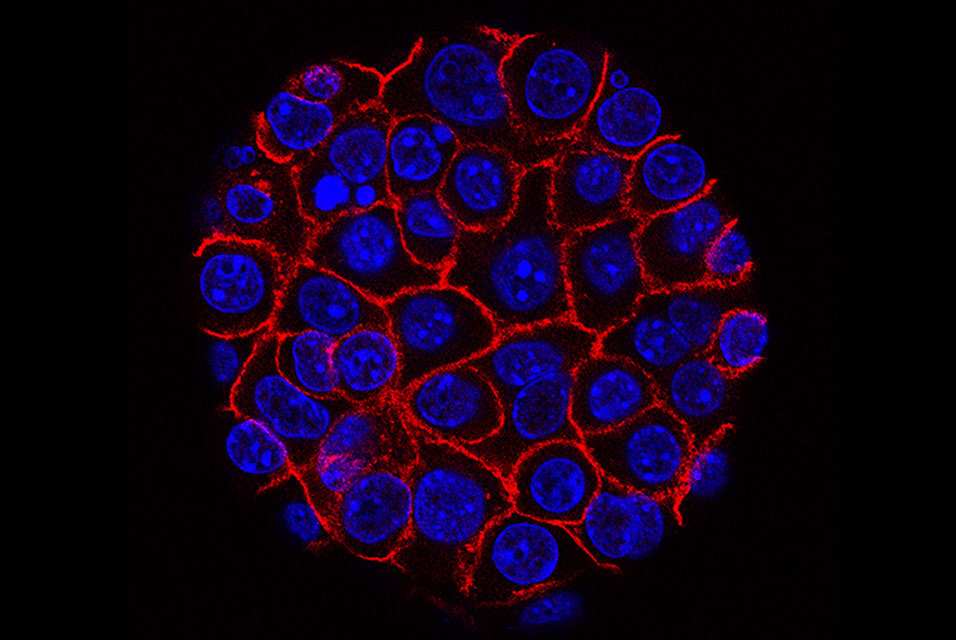

Specifically, the researchers found that the female brain shows higher expression of a certain enzyme compared to males, resulting in greater accumulation of a protein called tau. The tau protein is responsible for the formation of toxic protein clumps inside brain nerve cells of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

The enzyme, known as ubiquitin-specific peptidase 11 (USP11), is X-linked, meaning it is found in genes on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes in each cell.

“We are particularly excited about this finding because it provides a basis for the development of new neuroprotective medicines,” said David Kang, the Howard T. Karsner Professor in Pathology at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and co-senior author of a study published in the journal Cell. “This study also sets a framework for identifying other X-linked factors that could confer increased susceptibility to tauopathy in women.”

Alzheimer’s, women and tau

Women are afflicted by Alzheimer’s disease roughly twice as frequently as men. The mechanism behind this increased vulnerability is unclear, but one potential explanation is that women exhibit significantly higher tau deposition in the brain.

“When a particular tau protein is no longer needed for its nerve cell’s function, it is normally designated for destruction and clearance,” Kang said. “Sometimes this clearance process is disrupted, which causes tau to pathologically aggregate inside nerve cells. This leads to nerve cell destruction in conditions called tauopathies, the most well-known of which is Alzheimer’s disease.”

The process of eliminating excess tau begins with the addition of a chemical tag called ubiquitin to the tau protein. The presence of ubiquitin on tau is regulated by a balanced system of enzymes that either add or remove the ubiquitin tag.

Because dysfunction of this balanced process can lead to abnormal accumulation of tau in Alzheimer’s disease, Kang and co-senior study author Jung-A Woo, assistant professor at Case Western Reserve, searched for why this might happen.

Specifically, they looked for increased activity of the enzymatic system controlling the removal of the ubiquitin tag, because over-activation of this side of the balance could lead to pathological tau accumulation.

“We reasoned that if this could be identified, then it could provide a basis for the development of new medicine that could restore the proper balance of tau levels in the brain,” Kang said.

They found that women naturally express higher levels of USP11 in the brain than males, and also that USP11 levels correlate strongly with brain tau pathology in females but not in males.

Possible protection for women

The researchers also found that when they genetically eliminated USP11 in a mouse model of brain tau pathology, females were preferentially protected from tau pathology and cognitive impairment. Males were also protected against tau pathology in the brain, but not nearly to the extent as in females.

These results suggest that excessive activity of the USP11 enzyme in females drives their increased susceptibility to tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. However, the authors caution that animal models may not fully capture the tau pathology seen in humans.

“In terms of implications, the good news is that USP11 is an enzyme, and enzymes can traditionally be inhibited pharmacologically,” Kang said. “Our hope is to develop a medicine that works in this way, in order to protect women from the higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.”