PARIS.- Children born prematurely have a higher risk of cognitive and sensory disorders, but also infertility in adulthood. In a new study, a team of researchers from

Inserm, University Hospital Lille and Université de Lille at the Lille Neuroscience and Cognition laboratory has opened up interesting avenues to improve their prognosis.

By conducting research into a rare disease known as congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, the scientists have discovered the key role that an enzyme plays and the therapeutic potential of the neurotransmitter that it synthesizes—nitric oxide—in reducing the risk of long-term complications in the event of prematurity. Their findings are described in Science Translational Medicine. A clinical trial has also been launched at the Lille University Hospital in partnership with a hospital in Athens (Greece) in order to go further and measure the effect of nitric oxide on premature infants.

Congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is a rare disease characterized by delayed puberty or the complete absence of puberty in adolescence, leading to infertility. Some forms of the disease are caused by a lack of production of GnRH, a hormone produced in the brain that remotely controls the development and functioning of male and female gonads through various intermediaries.

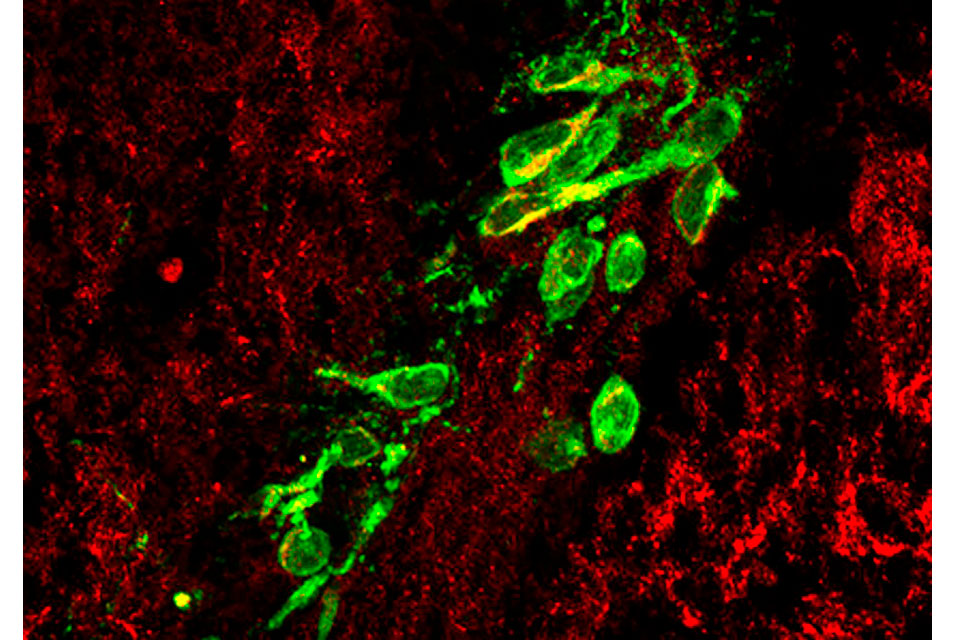

Inserm Research Director Vincent Prévot and his team study the dialogs between the brain and the rest of the body. Here the scientists looked at nitric oxide, a neurotransmitter that regulates the activity of GnRH neurons, and more specifically NOS1, the enzyme that synthesizes it. "Nitric oxide suppresses the electrical activity of the GnRH neurons and modulates the release of this hormone, so NOS1 dysfunction was not ruled out as being the cause of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism," explains Prévot, the principal coordinator of the study.

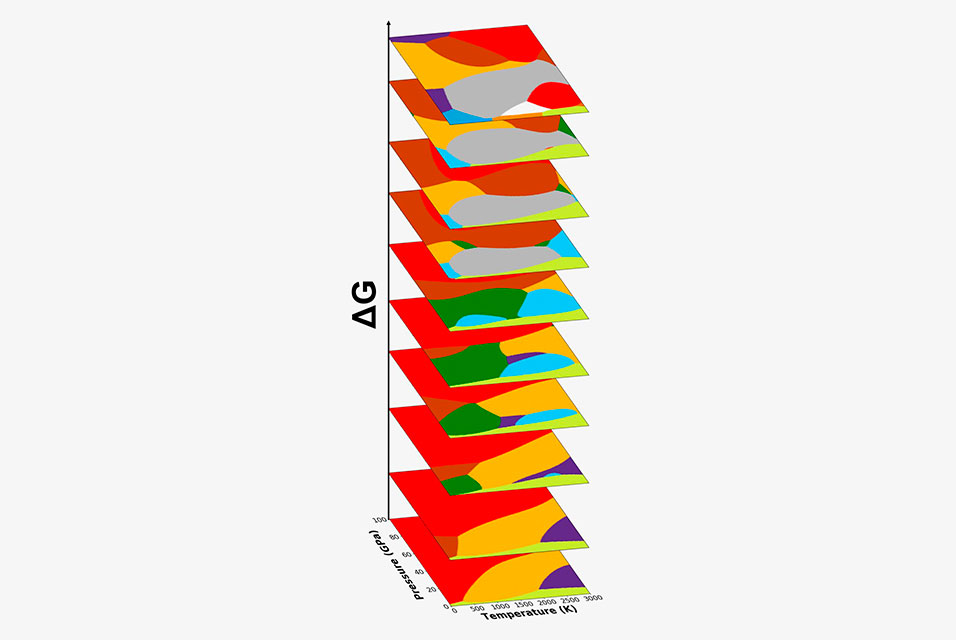

To go further, his team collaborated with a laboratory in Lausanne (Switzerland) which has a cohort of 341 patients living with this disease. Using DNA samples, the researchers looked for the presence of rare mutations on the gene encoding the NOS1 enzyme and found five different mutations that could explain the disease. Some of the individuals displayed, in addition to fertility problems, sensory and cognitive disorders (intellectual disability or loss of hearing or smell).

An application in the context of preterm birth?

The next stage of the study consisted of developing a NOS1-deficient mouse model in order to better understand the role of this enzyme. The researchers identified puberty problems, as well as sensory and neurological alterations in the animals, as is observed in humans with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

They also saw an exacerbation of minipuberty in these animals. Minipuberty occurs in all mammals just after birth (between one and three months of age in humans) and triggers an initial brain activation of the axis controlling reproduction prior to the "real" puberty which occurs in adolescence.

Here the researchers observed that the peak of the sex hormone associated with this minipuberty was twice as high in NOS1-deficient mice. "This caught our attention because premature infants also tend to present a more intense minipuberty than usual. And the greater the prematurity, the greater the risk of neurosensory and mental complications in adulthood," says Konstantina Chachlaki, Inserm researcher and first author of the study.

Based on these observations, the researchers tested the administration of nitric oxide in NOS1-deficient mice just after their birth, during the minipuberty period. What they saw was the reversal of all the symptoms they had developed: the puberty problems and sensory and neurological disorders disappeared. This was the case on the long term, for the remainder of their lives.

Launching a clinical trial

These promising findings could lead to an improvement in the care of preterm infants. Nitric oxide is alrady given to some children born prematurely, to facilitate the opening of the bronchi in the event of breathing difficulties.

"In light of this consistency of observations and practices, we decided to set up a clinical trial to test the effect of nitric oxide in preterm infants by studying reproductive and neurosensory parameters," explain Vincent Prévot and Konstantina Chachlaki, the coordinators of the minNO European project, which is dedicated to investigating the role of minipuberty in preterm infants.

"Administering nitric oxide at birth could reduce the risk of reproductive, sensory and intellectual complications in children born prematurely. This is what we are going to try to verify in the wake of these astonishing discoveries in mice."

The miniNO trial was launched at University Hospital Lille in partnership with a hospital in Athens (Greece). The objective is to verify whether children receiving this treatment go on to experience normal minipuberty and puberty, and whether they develop fewer sensory and neurological complications compared to premature infants who were not administered nitric oxide at birth. The aim of the clinical trial is to include 120 patients at the two locations (Athens and Lille) over 24 months.