AMHERST, MA.- A family of fishes called cichlids in Africa's Lake Malawi is helping researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst to refine our understanding of how evolution works.

In new research published in Nature Communications, co-authors Andrew J. Conith, postdoctoral researcher in the

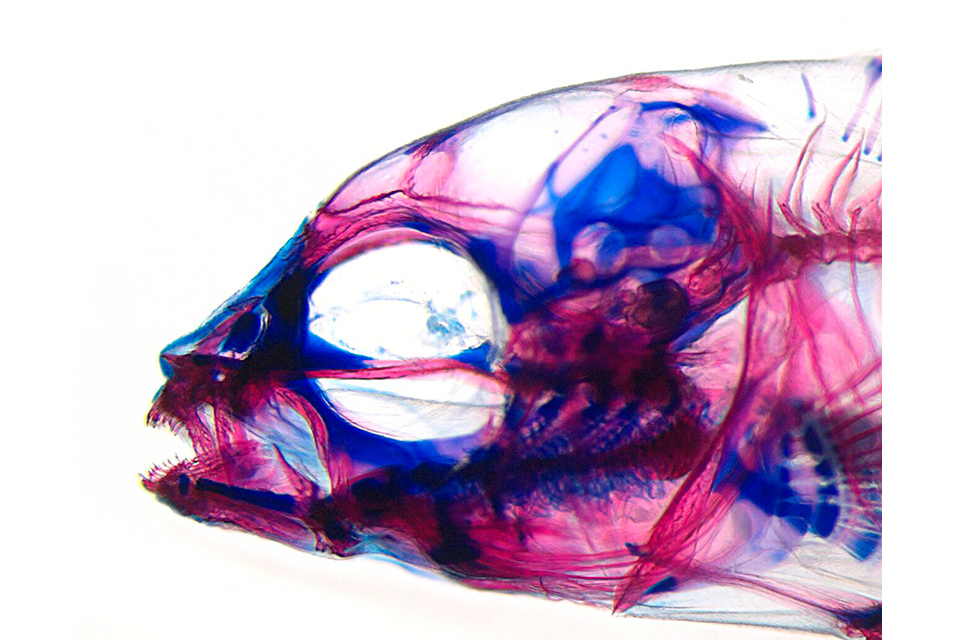

UMass Amherst biology department, and Craig Albertson, professor of biology at UMass Amherst, focus on the jaws of cichlids—which are notable because they have two sets of them.

"Remember the movie 'Alien,'" asks Conith, "when the alien is about to eat Sigourney Weaver's character? It opens its mouth and out comes a second set of jaws. Fast forward twenty years, and here I am, studying animals that have jaws in their throats."

Cichlids thankfully don't eat humans, but thanks to their twin pairs of jaws, they are a phenomenally successful group of fishes from an evolutionary standpoint. In Lake Malawi alone, more than 1,000 different species of cichlids have evolved over the last 1 to 2 million years. One set of jaws, the oral jaw, is similar to our own, and its role is to capture food. But cichlids, like the Xenomorph from "Alien," have a second set of jaws, deeper in their throats, that's made to process food once it has been captured by the first set. Having two pairs of jaws means that each jaw can specialize in a specific role, a feature that should increase their feeding efficiency and make them more evolutionarily successful.

Given the success of cichlids, understanding the evolution of these two jaws has become an important line of inquiry for biologists. "We're trying to gain a better understanding of the origins and maintenance of biodiversity," says Albertson. Researchers have long thought that the two sets of jaws are evolutionarily decoupled and can evolve independently of one another, pushing the boundaries of morphological evolution. However, Conith and Albertson demonstrated that such decoupling does not appear to be the case for cichlids, challenging a quarter-century-old assumption. "What we've found is not just that the evolution of the two sets of jaws is linked, but that they're linked across multiple levels, from genetic to evolutionary," says Albertson.

These findings are a significant step forward in better understanding how evolution works. For instance, many models of evolution theorize both that organisms are constructed from repeated units—digits on your hand or teeth in your mouth—and that these individual units evolve independently from one another. "It is this 'modularity' of organisms that is thought to facilitate the evolutionary process," Albertson notes.

Linked systems are usually thought to lack evolutionary potential. "They just cannot evolve in as many dimensions," Conith says. This is referred to as an evolutionary constraint, and it plays an important role in shaping biodiversity. Constraints determine what body structures are possible.

Remarkably, this constraint seems to be the key to cichlid's success by promoting rapid shifts in jaw shapes and feeding ecology, all of which is likely to be an advantage in a dynamic and fluctuating environment, like the East African Rift Valley, where Lake Malawi is located. "The constraint is actually facilitating cichlid evolution, rather than impeding it," says Conith.

"This tells us that we need to rethink the fundamentals of evolutionary mechanisms," says Albertson. "Perhaps constraints play a wider role in the evolutionary success of species around the world."