VANCOUVER.- A new study by researchers at the

University of British Columbia and the University of Victoria has shown that common levels of traffic pollution can impair human brain function in only a matter of hours.

The peer-reviewed findings, published in the journal Environmental Health, show that just two hours of exposure to diesel exhaust causes a decrease in the brain’s functional connectivity – a measure of how different areas of the brain interact and communicate with each other. The study provides the first evidence in humans, from a controlled experiment, of altered brain network connectivity induced by air pollution.

“For many decades, scientists thought the brain may be protected from the harmful effects of air pollution,” said senior study author Dr. Chris Carlsten, professor and head of respiratory medicine and the Canada Research Chair in occupational and environmental lung disease at UBC. “This study, which is the first of its kind in the world, provides fresh evidence supporting a connection between air pollution and cognition.”

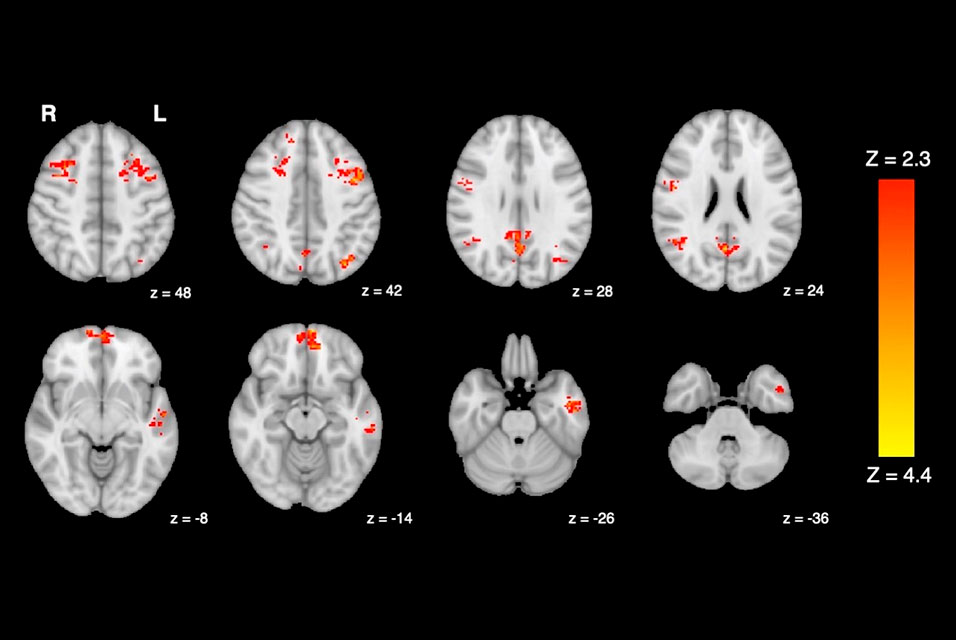

For the study, the researchers briefly exposed 25 healthy adults to diesel exhaust and filtered air at different times in a laboratory setting. Brain activity was measured before and after each exposure using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The researchers analyzed changes in the brain’s default mode network (DMN), a set of inter-connected brain regions that play an important role in memory and internal thought. The fMRI revealed that participants had decreased functional connectivity in widespread regions of the DMN after exposure to diesel exhaust, compared to filtered air.

“We know that altered functional connectivity in the DMN has been associated with reduced cognitive performance and symptoms of depression, so it’s concerning to see traffic pollution interrupting these same networks,” said Dr. Jodie Gawryluk, a psychology professor at the University of Victoria and the study’s first author. “While more research is needed to fully understand the functional impacts of these changes, it’s possible that they may impair people’s thinking or ability to work.”

Taking steps to protect yourself

Notably, the changes in the brain were temporary and participants’ connectivity returned to normal after the exposure. Dr. Carlsten speculated that the effects could be long-lasting where exposure is continuous. He said that people should be mindful of the air they’re breathing and take appropriate steps to minimize their exposure to potentially harmful air pollutants like car exhaust.

“People may want to think twice the next time they’re stuck in traffic with the windows rolled down,” said Dr. Carlsten. “It’s important to ensure that your car’s air filter is in good working order, and if you’re walking or biking down a busy street, consider diverting to a less busy route.”

While the current study only looked at the cognitive impacts of traffic-derived pollution, Dr. Carlsten said that other products of combustion are likely a concern.

“Air pollution is now recognized as the largest environmental threat to human health and we are increasingly seeing the impacts across all major organ systems,” says Dr. Carlsten. “I expect we would see similar impacts on the brain from exposure to other air pollutants, like forest fire smoke. With the increasing incidence of neurocognitive disorders, it’s an important consideration for public health officials and policymakers.”

The study was conducted at UBC’s Air Pollution Exposure Laboratory, located at Vancouver General Hospital, which is equipped with a state-of-the-art exposure booth that can mimic what it is like to breathe a variety of air pollutants. In this study, which was carefully designed and approved for safety, the researchers used freshly-generated exhaust that was diluted and aged to reflect real-world conditions.