PARIS (AFP).- Astrophysicists have detected a burst of cosmic radio waves within our solar system for the first time and identified its source, according to research published Wednesday that sheds new light on one of the mysteries of the Universe.

The origin of powerful fast radio bursts (FRBs) -- intense flashes of radio emission that only last a few milliseconds -- have puzzled scientists since they were first detected a little over a decade ago.

They are typically extragalactic, meaning they originate outside our galaxy, but on April 28 this year, multiple telescopes detected a bright FRB from the same area within our Milky Way.

Importantly, they were also able to pin down the source: Galactic magnetar SGR 1935+2154.

Magnetars, young neutron stars that are the most magnetic objects in the universe, have long been prime suspects in the hunt for the source of these radio bursts.

But this discovery marks the first time that astronomers have been able to directly trace the signal back to a magnetar.

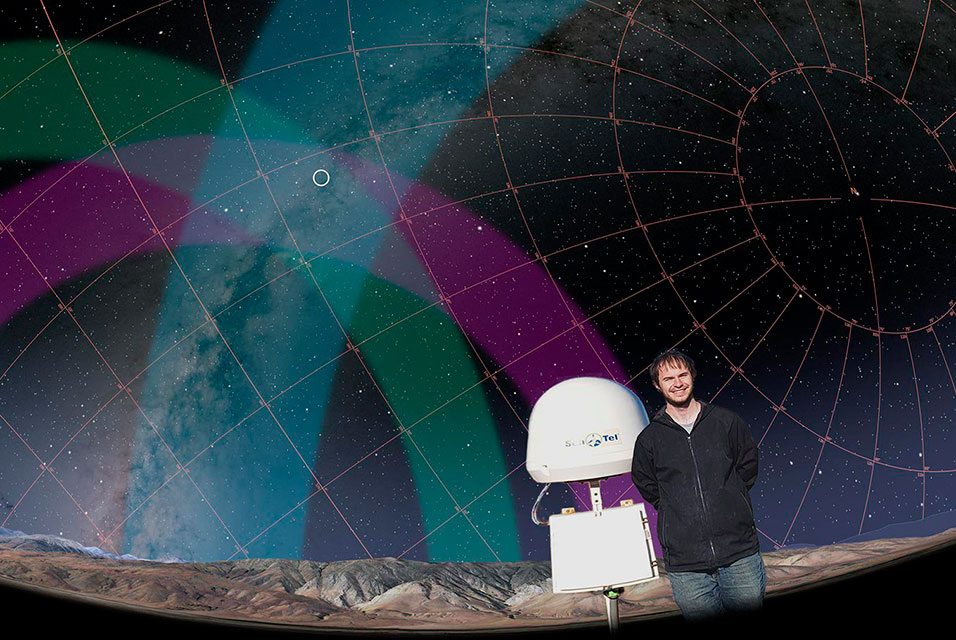

Christopher Bochenek, whose Survey for Transient Astronomical Radio Emission 2 (STARE2) in the US was one of the teams to spot the burst, said that in approximately a millisecond the magnetar emitted as much energy as the Sun's radio waves do in 30 seconds.

He said the burst was "so bright" that theoretically if you had a recording of the raw data from your mobile phone's 4G LTE receiver and knew what to look for, "you might have found this signal that came about halfway across the galaxy" in the phone data.

This energy was comparable to FRBs from outside the galaxy, he said, strengthening the case for magnetars to be the source of most extragalactic bursts.

As many as 10,000 FRBs may occur every day, but these high-energy surges were only discovered in 2007.

They have been the topic of heated debate ever since, with even small steps towards identifying their origin stirring major excitement for astronomers.

One problem is that the momentary flashes are difficult to pinpoint without knowing where to look.

Theories of their origins have ranged from catastrophic events like supernovas, to neutron stars, which are super-dense stellar fragments formed after the gravitational collapse of a star.

There are even more exotic explanation -- discounted by astronomers -- of extra-terrestrial signals.

'Key puzzle'

The latest discovery, which was published in three papers in the journal Nature, was made by piecing together observations from space and ground based telescopes.

Both STARE2 and the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) spotted the flare and attributed it to the magnetar.

Later the same day, this region of the sky came into view of the extremely sensitive Five Hundred Meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) in China.

Astronomers there were already keeping an eye on the magnetar, which had entered an "active phase" and was firing off X-ray and gamma ray bursts, according to Bing Zhang, a researcher at the University of Nevada and part of the team reporting on the discovery.

FAST did not spot the FRB itself, but it did detect multiple X-ray bursts from the magnetar, he told a press briefing, raising new questions about why only one of the bursts was linked to an FRB.

In a Nature commentary Amanda Weltman and Anthony Walters, from the High Energy Physics, Cosmology and Astrophysics Theory Group at the University of Cape Town, said the link of the FRB to a magnetar "potentially solves a key puzzle".

But they said the findings also open up a range of new questions, including what mechanism would produce "such bright, yet rare, radio bursts with X-ray counterparts?

"One promising possibility is that a flare from a magnetar collides with the surrounding medium and thereby generates a shock wave," they wrote, adding that the findings highlight the need for international cooperation in astronomy and the monitoring of different types of signals.

© Agence France-Presse